Prospecting for Gems of Bloomington's Past #17

Part II of Black People in Bloomington before the Civil War: From Notley Baker to Jacob and Smith Hawkins, conductors of the Underground Railroad

Notley Baker and his family….

Continuing our story from last week, former slave and barber, Notley Baker married Maria (Murriah, Moreah) before 1830. The Federal census for Monroe County indicates the couple had two girls by 1830, adding two boys and two girls by 1840.1 2 By 1850, they had only three surviving children, Sarah Ann (1830), Elizabeth (1837) and Martha J. (1843).3 Notley Baker apparently died around 1855, according to Moreah Baker’s estate documents.4 Sarah’s two younger sisters, Elizabeth and Martha, lived until after 860 with their widowed mother, but did not survive their mother who died around 1866.5 In 1850, Sarah Ann Baker had married a black man from Washington, Indiana, Smith Hawkins, the son of a former slave and a “conductor” in what was called The Underground Railroad. 6 (More details about Notley Baker can be found in Prospecting #2, #4, # 9, and #16.)

The Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

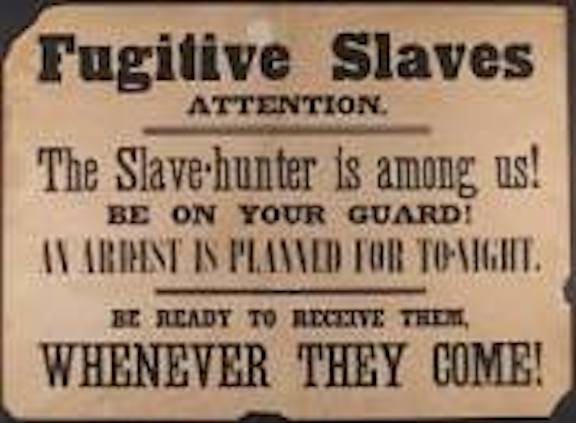

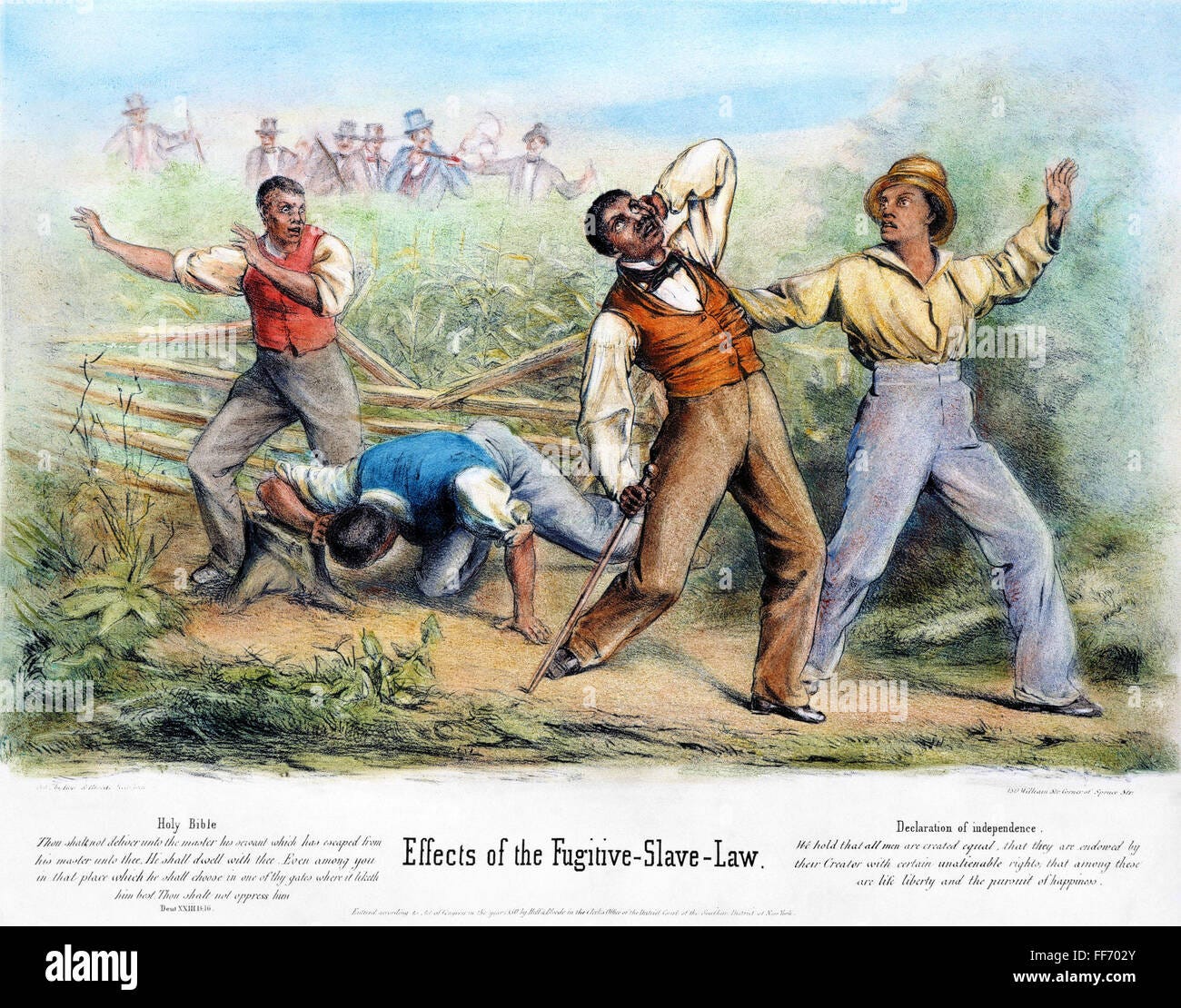

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established before the Civil War used by enslaved African Americans to escape into free states and Canada. The network was composed of white abolitionists and former slaves, called “conductors”. The need for secrecy was paramount as there was the danger of imprisonment or fines for those who helped fugitive slaves if they were caught and slaves would be returned to their masters. Therefore, railroad terminology was used to confuse the “slave catchers” 7 and records were not kept, making it difficult today for researchers to find our the details. Some slaves were able to escape on their own without the railroad network, but one estimate suggests that by 1850, approximately 100,000 enslaved people had escaped via the Underground Railroad. 8

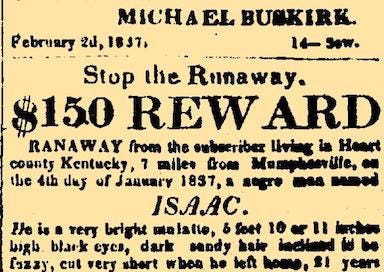

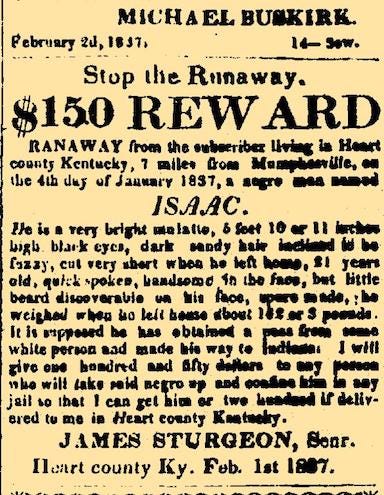

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, part of the Compromise of 1850, required that slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state. The act also made the federal government responsible for finding, returning, and trying escaped slaves. As a result, masters of escaped slaves hired bounty hunters or local “slave catchers”to find their missing property, often advertising in local newspapers. There was a danger, too, that freed blacks could be kidnapped and sold again in markets, usually in New Orleans.

“Jake”, Smith Hawkin’s father, was first indentured in Indiana

Born into slavery in Charleston, South Carolina, Smith Hawkin’s father, Jake, had been brought as a 13 year old by his owner, Eli Hawkins, to Knox County, Indiana Territory (today, Daviess County). They were among the first settlers in that area, and Indians were so numerous, that a fort was built for safety. Since slavery had been outlawed in the Northwest Territories, including Indiana, Eli Hawkins and other slave owners got around anti-slavery laws by making his slaves indentured servants. Slaves, who could not read or write, were forced to “sign” the agreements. An indenture for 90 years was signed in 1805 with the Knox County, Indiana Clerk of Common Pleas involving Jake. He would have to live to be 106 to see his freedom.9

“Jake” Hawkins freed in 1821

When Eli Hawkins died unexpectedly in 1816, Mrs. Catherine Hawkins married William Merril, who considered his wife’s servants his marriage property and treated them poorly. Instead of running away, Jake and another indentured servant, Isaac, approached an abolitionist lawyer, Amory C Kinney, who had won the famous “Polly Case” before the Indiana Supreme Court. Kinney sued the Merrils for the freedom of Jacob and Isaac and won the case on September 21, 1821. Jacob and Isaac were freed, as were the other slaves in that county. If they had run away instead of going to court, the other African-Americans in the county would have remained enslaved. 10

Jacob took the last name of his former owner, Hawkins, and married Ellen “Nelly” Embers on November 21, 1821, another. freed slave. The couple had 11 children. (“Smith” Hawkins was their second child, born in 1829.) Jacob became a very prosperous and successful citizen in Daviess County and, over time, he amassed a thousand acres, buying his first plots of land around 1831, over thirty years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Hawkins founded the town of Maysville, Indiana and was also one of the founders of the Beulah African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, Indiana along with his wife Ellen. 11

Two of their sons, Charles (Smith’s elder brother) and Charner (his younger brother) were original members. Jacob played a key role in the local development of the Wabash-Erie Canal in the area and sold land to the railroad.

The Hawkins Family become Conductors through Bloomington

Living near the Kentucky border, Jake Hawkins aided many fugitive slaves when they passed through the area to freedom. Apparently, his whole family was involved, including Smith and his wife, Sarah Ann. Sarah Hawkin’s father, Notley Baker, a barber in Bloomington for many years, knew all the abolitionists in town who might be willing to help fugitive slaves, so he introduced them to his son-in-law. Hawkins brought many runaway slaves through Bloomington on their way north and assisted Thomas Smith in running the Underground Railroad in Monroe County.12

While the route above between Maysville and Bloomington follows the present I-69, the conductors might have taken their “passengers” through Bedford, where there was a large group of black residents living in Shawswick Township, where they could find food and shelter before going north to Bloomington. A woman named Hannah Collins Breckinridge McCaw was born there, married a former slave, and lived in that township among other African Americans until the mid-1850’s.. Her grandson, Willis O Tyler, famed orator, lawyer and judge, was raised by Hannah McCaw in Bloomington. He claimed that she was a “conductor” of the Underground Railroad.13

Sarah and Smith Hawkins had one daughter, Elizabeth, born in 1850. Some time between 1850 and 1854, Sarah Ann Baker Hawkins died, as Smith Hawkins married Sarah Goens July 30, 1854. His other nine children were born of his second wife. (Since both wives had the first name, Sarah, it has been confusing. According to Moreah Baker’s estate documents, her granddaughter, Elizabeth Hawkins, was her only survivor.) Other clues indicating a second “Sarah” are that her birthdate and birthplace (1836, Alabama) from the federal censuses of 1860, 1870 and 1880 for the Hawkins family differ from Sarah Baker (born 1830 in Indiana).

Sarah Goins and Smith Hawkins can be found in the 1860 Federal Census for Richmond, Indiana, where he worked as a laborer. They returned to the family farm in Daviess County some time before 1870, probably at the time of his father’s death in 1864, and stayed in that area until their deaths. (Smith Hawkins died in 1885, and his second wife, in 1884.) They are both buried at Hawkins Cemetery, just northeast of Maysville, Indiana. One can only speculate as to how long Hawkins worked with the Underground Railroad, since both Sarah and Notley Baker died by 1855. However, it is possible Smith Hawkins met his second wife while involved with the Underground Railroad, as the couple were married in Evansville.As it turns out, Richmond had a thriving colony of Quakers who were active with the Underground Railroad, so that is probably why the Hawkins moved there. (This paragraph has been revised since this history blog was published earlier today.)

When the Civil War broke out, Smith served in the 28th U S Colored Infantry as a private. Fortunately, he survived the war although many of his contemporaries did not.

There are descendants of Jacob and Ellen Hawkins still living on part of the original farm of Eli Hawkins, and his former slave, Jake Hawkins. It is a 39 acre farm in Daviess County now owned by black farmer, Donald Cottee and his wife, Charlet. He’s on a mission to learn all he can about the history of his 39-acre farm, one of the oldest continuously owned family farms in the state, even predating Indiana’s statehood. “I’m fortunate. There’s not many farms that have been in the family that long,” Cottee says. And particularly not many farms owned by African American families. 14 When Jacob Hawkins and then Ellen, his wife, died, their property was divided up among their 11 children, including the daughters. In fact, their middle daughter, Eliza Ann Hawkins, is Donald Cottee’s great-grandmother. Below is a picture of some of Cottee’s family who lived on this farm in the early 20th century.

1830 Federal Census for Monroe County, Indiana. Year: 1830; Census Place: Monroe, Indiana; Series: M19; Roll: 30; Page: 13.

1840 Federal Census for Monroe County, Indiana. Year: 1840; Census Place: Monroe, Indiana; Roll: 99; Page: 77;

1850 Federal Census for Monroe County, Indiana.Year: 1850; Census Place: Bloomington, Monroe, Indiana; Roll: 161; Pages: 219b, 220.

Monroe County Probate Re.cords. Index: 1818-1960. Baker, Moreah Estate, p 10, folder 19.

1860 Federal Census for Monroe County, Indiana. Year: 1860; Census Place: Bloomington, Monroe, Indiana; Roll: M653_282; Page: 726.

Monroe County Marriage Index, 1818-1881: Smith Hawkins and Sarah Ann Baker, 12/08/1850, Bk. B, Page 213.

Wiipedia: The Underground Railroad. Accessed July 31, 2022.

Vox, Lisa, "How Did Slaves Resist Slavery?" Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine: African-American History, About.com,Accessed July 17, 2011.

A pamphlet, Along The Road To Freedom, by Dan Donofrio about the Underground Railroad in Daviess County, Indiana, p 3.

History of Daviess County, Indiana: Its People, Industries and Institutions ... with Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens and Genealogical Records of Many of the Old Families. (1915). United States: B. F. Bowen.p 139.

History of Knox and Daviess County, Indiana: from the earliest time to the present; with biographical sketches, reminiscences, notes, etc. ; together with an extended history of the colonial days of Vincennes, and its progress down to the formation of the state government. Chicago: 1886.Goodspeed, pp. 882, 913.

Henry Lester Smith, Ph.D., "The Underground Railroad in Monroe County," Indiana magazine of history, September 1, 1917, p 291.

"Oratorical Contest: Mr. Willis O. Tyler Represented The Indiana University," Indianapolis Recorder, February 9, 1901.

Edible Indy,: Foraging through History. https://edibleindy.ediblecommunities.com/food-thought/foraging-through-history. Accessed July 30, 2022.

After I wrote this article, I found found out that Richmond was an important stop on the Underground Railroad because a colony of Quakers lived there. That might explain why the Hawkins family moved there by 1860.

This is wonderful! Thank you so much for your work. I have a few photos of these locations, I would be happy to email them to you. Hawkins Prairie Cemetery was beautiful, and there are many admirable headstones therein. Quite a few Cottees are buried there too - the prominent name Cottee was also mentioned by Eunice Brewer-Trotter in her book "Black in Indiana". She is a descendant of Mary Bateman Clark in Vincennes. There also is a Breckenridge Cemetery in Bedford where Dive and Ruvina (Hannah McCaw's mother, if I remember correctly) lie buried. I found a reference of Halson V Eagleson and his wife visiting his friends in Bedford (mentioned in the Indianapolis Recorder, I need to look this up again). I think Hanna Collins McCaw's house is the one on Eighth and Grant Street here in Bloomington. Thanks again!