Prospecting for Gems of Bloomington's Past #4

How a black barber became part of the Underground Railroad in Bloomington

Christine Friesel of the Indiana Room at MCPL first introduced me to Notley Baker. by showing his listing in the 1850 census with his wife, Murriah (Moreah) and three children.

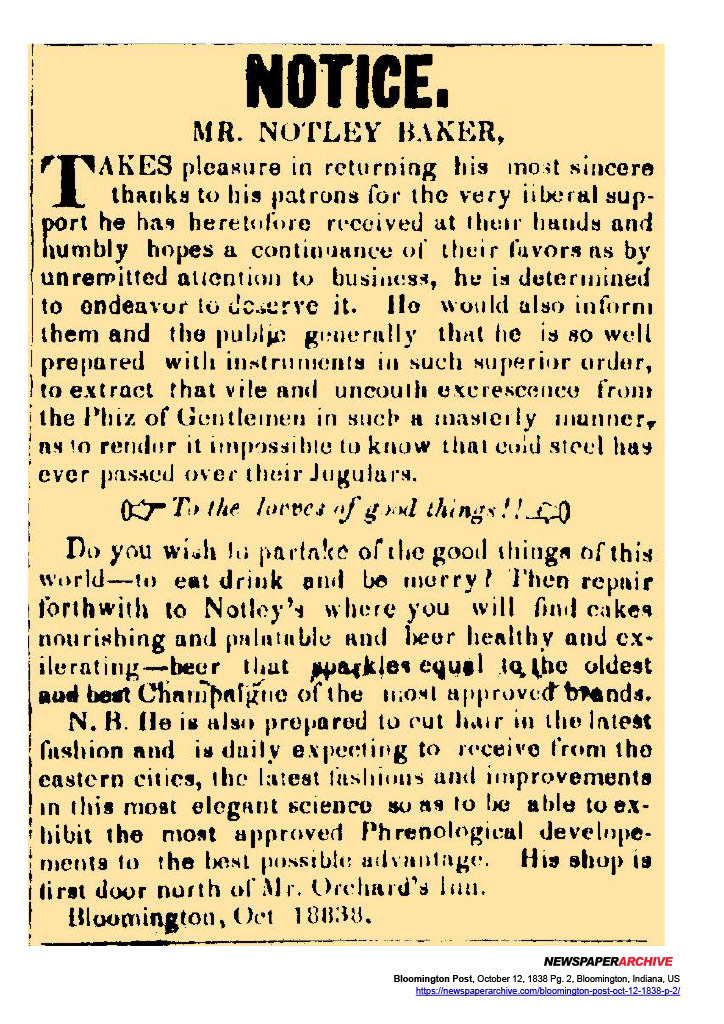

Notley Baker (also, Nolty, Natty, Nolley) was the first barber of any color and one of the first liquor sellers in Bloomington in 1827. You will notice in the following ad that both food and alcohol were available in his barber shop. The ad is notable as he could not read or write (see the 1850 census information for Notley Baker in posting #2). The language and sarcasm in the ad indicates he was probably attempting to attract “high class” customers. 1

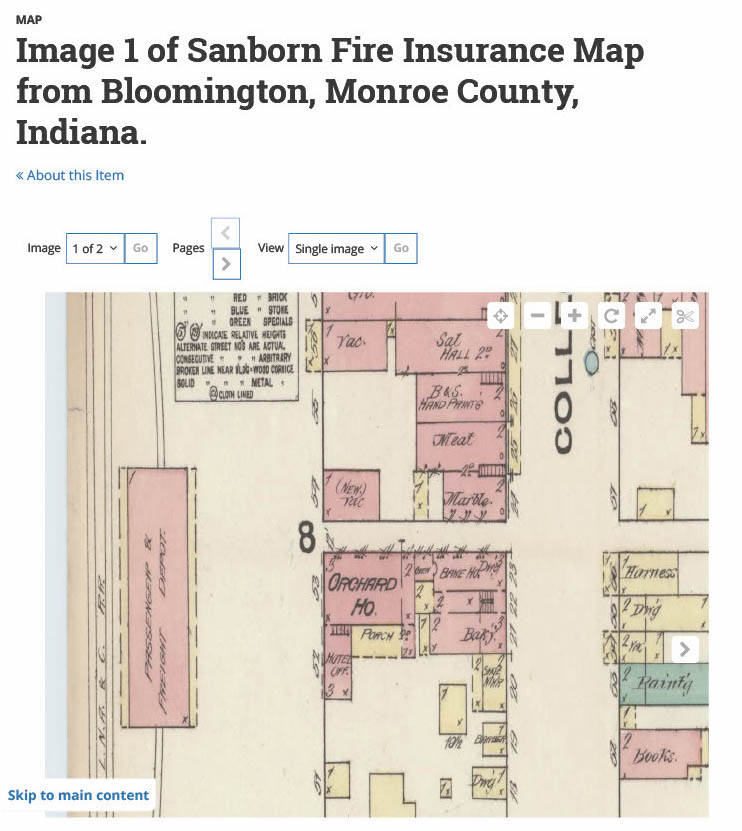

His shop was located at the first door north of Mr. Orchard's hotel across from the railroad depot in downtown Bloomington. That would be the first brick building north of “Orchard Ho” on the following map:

His business was listed as one of the first businesses in town. Several entries about him can be found on the Monroe County Timeline . Baker and his family lived near downtown and were listed in the 1840, 1850 and 1860 Federal Censuses.

How did a black man get to Bloomington, a very white town? A descendant of David H. Maxwell (the “Father of IU”), Martha Maxwell Howard, wrote down memories of old Bloomington in 1907, stating that the first barber was a "colored man by the name of Notly (sic) Baker" and this Mr. Notley Baker was owned by Mr. Joshua Howe, who brought him from Kentucky.2 Of course, I had to find out what I could about Joshua O Howe, who will be the subject of a future blog. For purposes of this story, we will limit our information to the fact that Howe (and, probably, Baker) arrived in Bloomington from Kentucky in 1819. Howe was one of the first landowners in the county and established one of the first dry goods stores on the square. Baker had to be freed from slavery in Indiana, although he could be employed as a servant.

Even though slavery was prohibited in Indiana as part of the Northwest Territories, local counties got around the prohibition by an indenture law, the indenture often lasting a lifetime. Ex-slaves generally could not read or write, so they had little power. Notley appears on the scene in town in 1827, so it is unclear when he was freed.

Mr. Smith Hawkins, a black man from Washington, Indiana, married Sarah Ann Baker the daughter of Notley Baker on Dec. 8, 1850 in Bloomington. 3 The clergyman was a G C Smith from the Bethel Lane Methodist Church. Hawkin’s father, Jake, had been brought as a slave/indentured servant to Davies County, Indiana in 1806 by his master, Eli Hawkins. Jacob continued to serve the Hawkins family until afterMr. Hawkins died when his widow married a man who became a difficult master. At that time, Jake and another slave, called Isaac, filed a lawsuit challenging the legality of their indentured servitude, and won the case. After being freed from indenture in 1821, Jacob Hawkins became a prosperous farmer, owning over 1000 acres of property decades before the Civil War. When Smith Hawkins, eldest of Jacob’s nine children, married the daughter of Notley Baker, he made contact with men Notley knew in town who were willing to help escaped slaves. Hawkins was involved with the Underground Railroad network by giving the fleeing slaves directions and assistance on their journey north toward Thomas A Smith’s house in Bloomington. 4 Fugitive slaves often were given food and shelter at the Smith residence on Pickwick Place, near the Covenanter Cemetery at High and Moore’s Pike (built in 1828, it still exists). Sometimes, they stayed long enough to be taught to read and write.

Below is a picture of a younger brother of Smith Hawkins, Charner Hawkins. The Hawkins farm near Washington, Indiana, was close to a river area where escaping slaves sometimes hid from slave catchers. The whole Hawkins family was involved in the movement, as Jacob Hawkins knew what it was like to be a slave.

In 1831, Notley Baker bought Seminary Lot #24, and then sold it to his former master, Joshua O Howe the following year.5

The probate records in 1866 for Moreah Baker, Notley’s wife, indicate that she made an agreement to do the laundry of Joshua O Howe at $12 a year (or, $1.00 a month) in 1855 in exchange for the loan of $200 to buy In-Lot #51 in Bloomington. The laundry work was done between June 9, 1855 and Nov. 18, 1863 and she died in 1865 or 66. She was unable to pay the principal and did not finish paying for the interest accrued on the loan by her laundry work. The lot was probably one that Howe had previously owned. After Moreah Baker’s death, it was sold to Howe’s son, James, so Moreah “borrowed” it for a few years. There are no probate records for Notley Baker, but it is assumed he died in 1855. Sarah Ann Baker Hawkins was the only survivor of the three Baker children. 6

Here is a screen shot of Moreah Baker’s ln-Lot #51 next to the railroad tracks It would have been the second lot in from 4th St. on the westside of the B Line Trail.

Bloomington Post, Oct. 12,1838. p.2.

Martha (Maxwell) Howard, An Early Sketch of Bloomington and the Family of David H. Maxwell: Part IV from Lilly Library transcript (1907).

Henry Lester Smith, Ph.D., "The Underground Railroad in Monroe County," Indiana magazine of history, September 1, 1917, 291.

Quite fascinating.

But it seems quite a leap to extrapolate from an 1838 newspaper clipping to the 1883 Sanborn map that was used above. A lot can happen in 45 years. The Orchard House would burn to the ground just five years later, in 1888.

I am so excited that you wrote about Knolly Baker! It's so great that you were able to find the locations, too. I had no idea!

I have a few questions about Knolly. Maybe you have some ideas.

It is possible Knolly was freed with intent by Mr Howe once they came to Indiana, but I wonder if maybe "Ole Knolly" successfully sued for his freedom based on the ruling that indentured servitude is slavery.

Precedent was set by two famous self-emancipators: Mary Bateman Clark (1920) and Jacob "Ole Jake" Hawkins (1823). It is the same Hawkins whose son went on to marry Sarah Ann Baker. Hawkins is the very first name in the "slave book" in Vincennes Indiana. The story of Hawkins is incredible, we visited his grave in Washington, Daviess County. https://edibleindy.ediblecommunities.com/food-thought/foraging-through-history

In the same sources which you sited, it mentions two "Marias" as well as Mrs Myrears (specifically mentioned in Henry Lester Smith's Underground Railroad). One Maria was brought from Kentucky, I'm guessing Knolly's wife who came with the Howe household, and the second Maria who was brought from Maryland by Mr Rawlins.

I've started to wonder if Mrs Myrears might be Maria from Maryland. I understand she lived at the site of the electric light plant (1917) on S Rogers. by the "Monon Yards". This makes sense because her farm would have been located on the way out of town towards Sam Gordon's House; he was a collaborator in the Underground Railroad; and heading East, past the Faris House on Hillside and the Smith House on Pickwick. She must have been working with the Covenanter Families. She's also called Aunty Myrears, which could mean that Myrears is a first and not a last name. Maria can also be pronounced two different ways: mah-ree-ah and mah-ri-yah. Knolly's wife's name is also spelled Moreah in the 1850.

Knolly's name also experienced extreme spelling variations.

These are my humble theories, but I would love to see if you can make sense of this, too.

Wonderful post!