Prospecting for Gems of Bloomington's Past #9

A Return to Professor Baynard Rush Hall and "colored" people, such as former slave, Notley Baker...

Having just finished the wonderful biography, Baynard Rush Hall: His Story by Dixie Kline Richardson, 1 I would like to discuss Hall’s relationship with black people during his lifetime. As you might recall, Baynard Hall was the only professor at the new Indiana State Seminary when it first opened.

Let’s get a little perspective on this complex man. Hall was left an orphan in 1800 just three days shy of his third birthday upon the death of his father, Dr. John Hall. (It is likely his mother had died the previous year). Dr. Hall’s will specified that “Old Daphney” Peterson would continue to be his son’s nurse. She was a freed slave who had dedicated her life to the Hall family and Baynard had a very close and loving relationship with this woman who became his “mother” as well as his nurse. His biological mother, Elizabeth Ann Baynard, had come from a slave-holding, plantation-owning family on Edisto Island, SC, where the cotton-growing slave population in the thousands vastly out-numbered their white masters. Elizabeth had married Dr. John Hall of Philadelphia who had served George Washington during the Revolution.

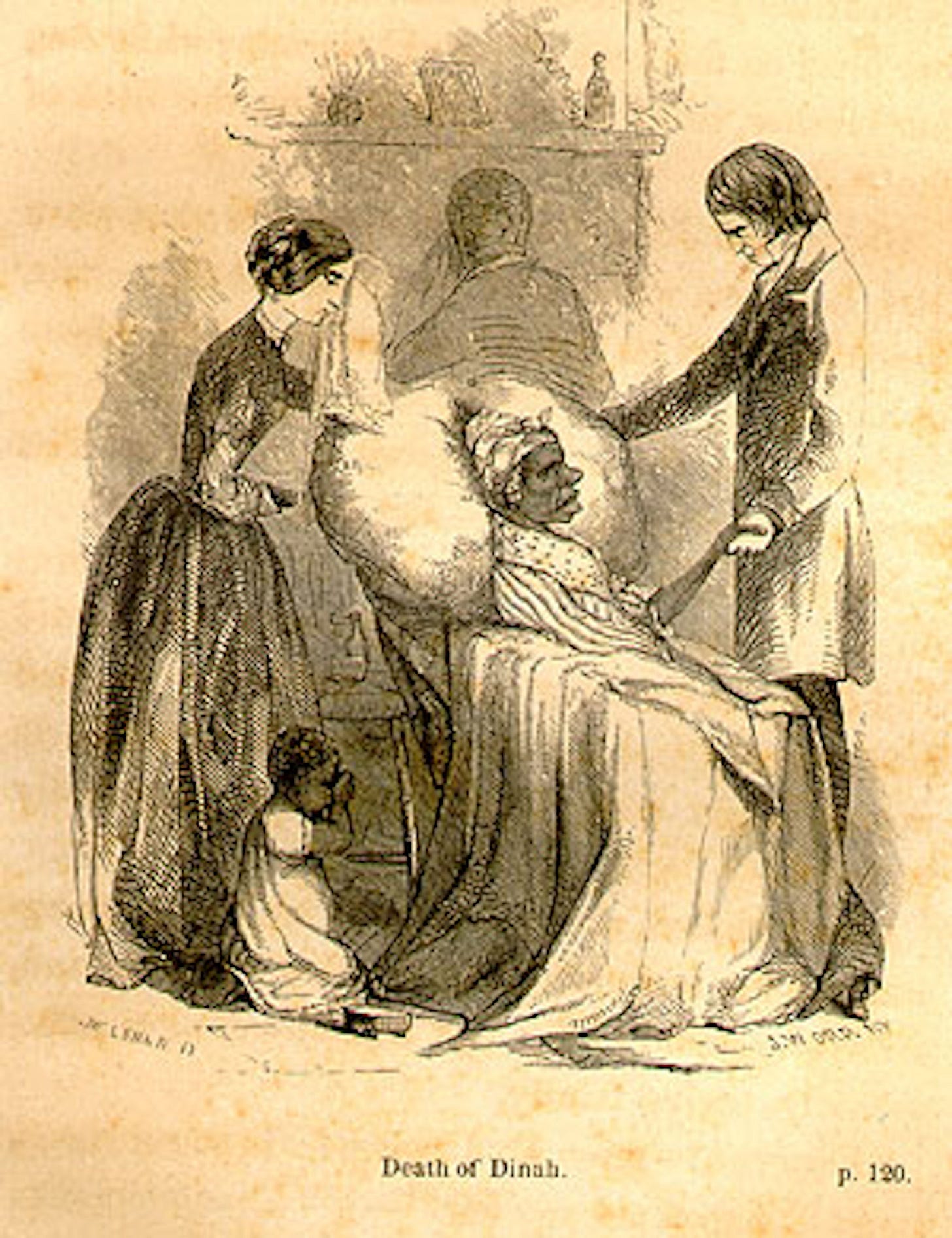

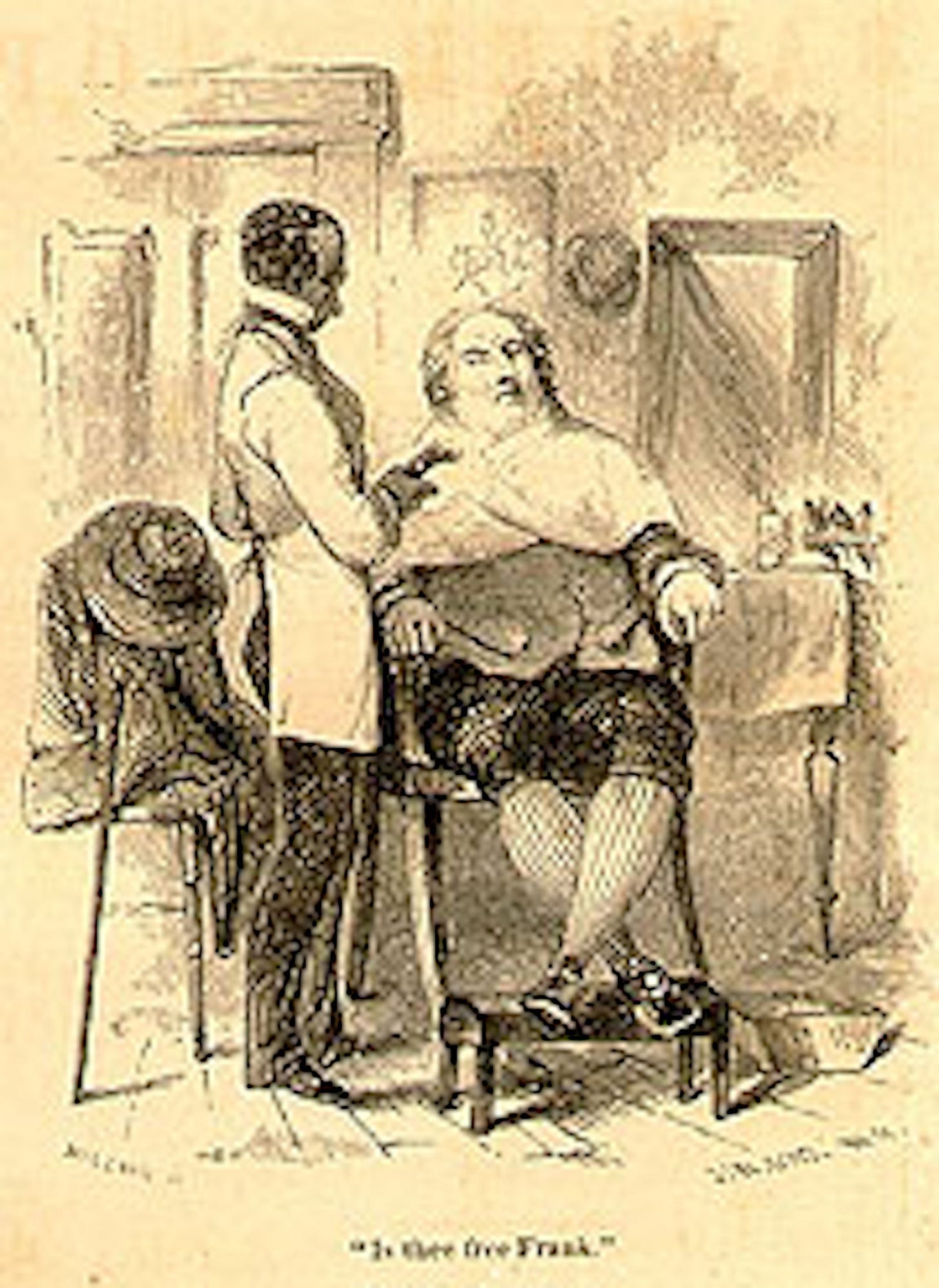

Young Hall lived with Daphney until he was old enough to be sent to boarding school, while the eminent, chosen “guardian” and signer of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Rush, declined the responsibility, but helped with his cousin’s education from afar. Hall’s “early induction into the caring master, loyal and loving servant experience was the seedbed for Hall’s slavery stance and led to his novel, Frank Freeman’s Barbershop in which a character named Dinah was the personage based on Daphne Peterson.”2 The illustration below is from Frank Freeman’s Barbershop.

When Hall and his wife passed through Bloomington around 1823 on their way to Owen County to live with his wife’s relatives (before he was officially hired to teach at the new Indiana State Seminary), the couple were subject to stares by the locals as Baynard was cleanly shaven and wore a coat and Mary Ann didn’t wear the usual cap of married women. This was an early indication of “town-gown” and class issues in Bloomington, but, apparently, even the best class in town didn’t shave more than once a week. A descendant of David H. Maxwell (the “Father of IU”), Martha Maxwell Howard, shared memories of early Bloomington in 1907. One memory among many was that the first barber was a "colored man by the name of Notly (sic) Baker" and this Mr. Notley Baker was owned by Mr. Joshua Howe, who brought him from Kentucky.3 Baynard Hall was destined to meet Notley Baker sooner or later and to need a shave.

A few years later came the “Pig in the Parlor Incident” which filled an entire chapter (Chapter LV/Fifth Year) to relate in Hall’s book, The New Purchase, 4 but it was also mentioned by Martha Maxwell Howard and by Martha McCollough, who wrote Pioneer Tales of old Bloomington. During a family wedding on May 6, 1829 as Baynard R Hall was officiating, some 200+ disgruntled, uninvited and, perhaps, inebriated folks performed what was called, a “Shiveree” using pans, cow bells, and other noise-makers outdoors to make a clamor as a practical “joke” after the ceremony. In the midst of the pandemonium, a 6 month old pig was thrown through a window into the parlor, upsetting tables of food and scattering guests. A black person hired to serve food for this occasion was called “Woolley Ben” in Hall’s book, “the only respectable ‘nigger’ in town”, 5 but later was identified as“Noble Baker” by James Woodburn in his annotated edition of The New Purchase. The name, “Notley” was so unusual that about a half dozen variations of the name are in print in census records, land transactions, and news articles, including “Nolly”, “Natty”, “Noltey”, and “Noilsey”, so “Noble Baker” is not much of a stretch.

As we return to the book Hall wrote in 1852, Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop.6, my personal opinion is that Notley Baker was the real person behind the caricature of Frank Freeman. Hall’s son, Rush, a gifted artist, drew the illustrations for its publication just two years before dying of TB. It is possible his father had some input into the drawing of the black man, perhaps thinking of the barber he knew long ago. “The story focuses on a slave named Frank, who is convinced to run away from his peaceful life on a Southern plantation by "philanthropists" (Hall's term for abolitionists), having been promised that freedom would also bring a prestigious career. When Frank comes to the end of his journey, however, he realizes that he has been deceived: his prestigious career is nothing more than running a seedy barber shop frequented by his new abolitionist masters, and is paid meagre wages for his work. However, Frank is soon discovered by members of the American Colonization Society, who rescue Frank from his predicament and pay for his passage back to Liberia, his homeland, where he can finally live in peace.” 7

For more information on The American Colonization Society I would recommend clicking this link to Wikpedia. Many of Baynard Rush Hall’s contemporaries were in sympathy with the Society which attempted to solve the problem of what to do with ex-slaves by shipping them off to Africa. (This includes Henry Clay and Joseph Albert Wright, a very poor but hardworking former student of Hall’s in Bloomington, who rose from humble beginnings to become a successful lawyer, state Representative, state Senator, Governor of Indiana, and was ultimately appointed by two presidents as special envoy to Prussia.) I believe that Hall had sincere but misguided motives in promoting the work of this organization. His book about Frank Freeman is classified as “anti-Tom literature” and Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published about the same time. He wanted the public to know that many slave-owners were not evil, as depicted in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and he must have honestly thought ex-slaves would be better off in Africa. It happens that some members of the American Colonization Society were actually abolitionists. Of the 4,571 emigrants who arrived in Liberia between 1820 and 1843, only 1,819—40%—were alive in 1843. Liberia was not a healthy place to live and it was very expensive to pay for passage, food, and support. Most free blacks declined the “opportunity” to emigrate. It seems that many white people in the early to mid 1800’s were already concerned with the “Browning of America”!

In his declining years, Baynard Hall taught young black children in Brooklyn, NY. Perhaps he really still had a heart for black folks after all.8

As a last note, I have researched the possible location of the “Pig in the Parlor” incident, prompted by a footnote on page 450 in the James Woodburn version of The New Purchase.

The lot described above is #44 at the corner of 4th and College of the original plat of Bloomington Township was owned in 1829 by Joshua O Howe and was transferred to Louisa Howe Maxwell and husband, James D Maxwell in 1848, five years after their marriage.9 The Howes, Maxwells, and Halls were all in the same social circle, so it is not surprising that the Howes would host such an important social event for the Hall’s extended family. The anger expressed in the incident shows there was considerable “town-gown” resentment on the town side of the equation.

Richardson, Dixie Kline, Baynard Rush Hall: His story, @ 2009, Dixie Kline Richardson. ISBN: 978-0-615-3636316-5.

Richardson, Dixie Kline, Baynard Rush Hall: His story, @ 2009, Dixie Kline Richardson. ISBN: 978-0-615-3636316-5., p. 20.

Martha (Maxwell) Howard, An Early Sketch of Bloomington and the Family of David H. Maxwell: Part IV from Lilly Library transcript (1907).

Hall, Baynard Rush, 1798-1863. The New Purchase: Or, Early Years In the Far West. 2d ed., New Albany, Ind.: J.R. Nunemacher; [etc., etc., 1855, p 425.

Pioneer tales by Margaret J McCollough, History of Lawrence And Monroe Counties, Indiana: Their People, Industries, And Institutions. Indianapolis: B.F. Bowen, 1914, p 453.

Hall, Baynard Rush, 1798-1863. Frank Freeman's Barber Shop: a Tale. [S.l.]: Auburn, Alden, Beardsley & co., 1853.

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Freeman%27s_Barber_Shop (accessed May 29, 2022.

Rousmaniere, John, Green Oasis in Brooklyn: The Evergreen Cemetery 1849-2008.

Monroe County Deeds, Book K, Page 597.